New book translation in Bosnian.

"Svitanje u ocima Snjeska Bijelica" i

"Vjetar u ludackoj kosulji"

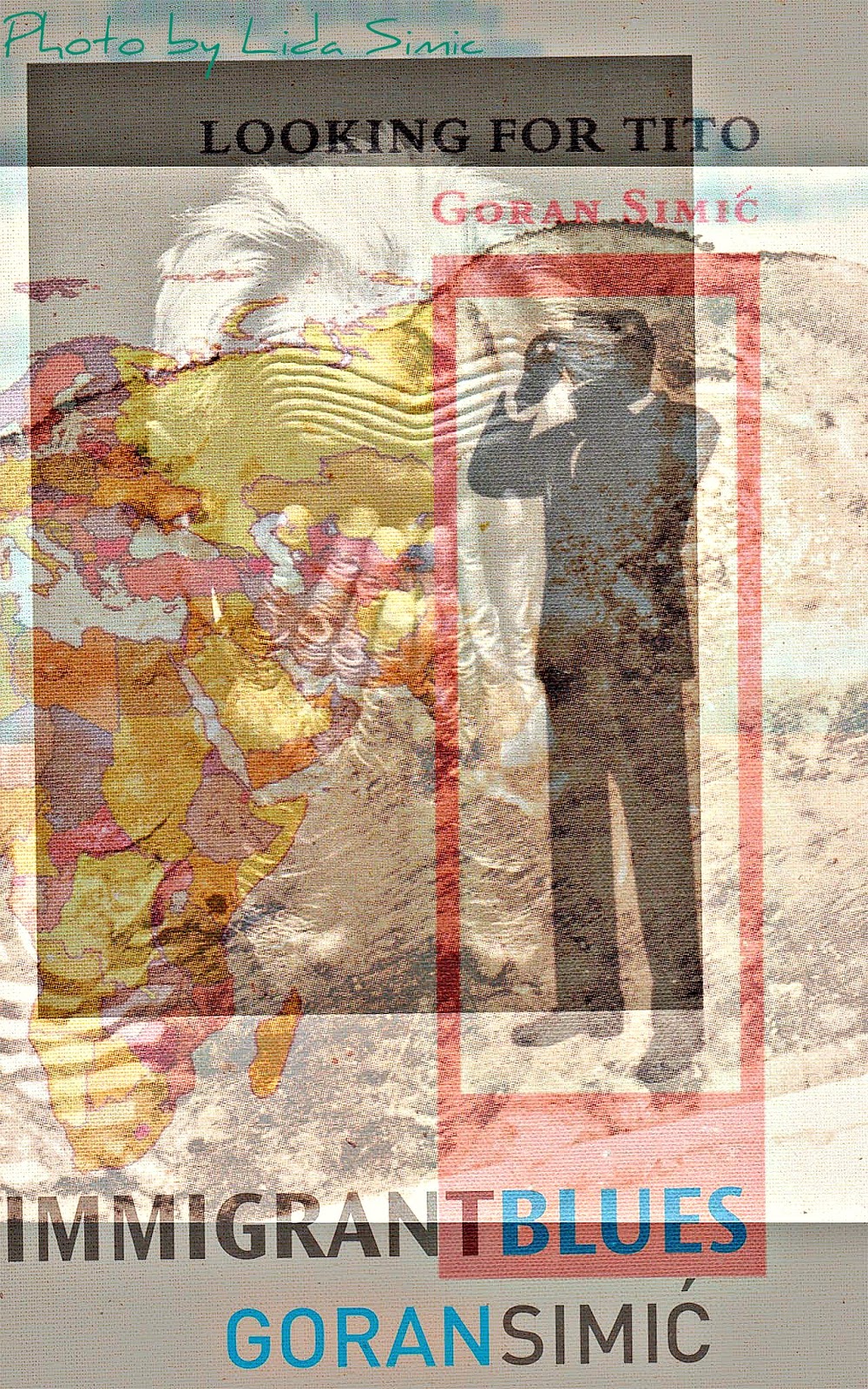

IMMIGRANT BLUES

BEFORE YESTERDAY TURN TO BE TOMORROW PRIJE NEGO STO SE JUCE PRETVORI U SUTRA

Thursday, April 4, 2013

Monday, July 23, 2012

Prairie Fire Review of Books..review of Sunrise in the Eyes of the Snowman

Vol. 11, No. 3 (2011)

Reviewed by Anna Mioduchowska

I was a boy just yesterday.

I am the ghost of the house today,

growing up languid as a hothouse flower,

or a lizard daydreaming of becoming a dragon. (20)

Poet does not appear on Immigration Canada’s list of preferred occupations, and not surprisingly,

poets who have achieved some degree of success in their homelands rarely choose to emigrate in

times of peace. We have the civil war in former Yugoslavia, and PEN Canada, to thank for Goran

Simic's presence among us.

Sunrise in the Eyes of the Snowman

launched during Simić’s appointment as Edmonton’s Poet in-

Exile, is his fifth collection of poetry since his arrival in 1996 from Bosnia-Herzegovina, and his

first written in English. In the Acknowledgements he calls it “my private poetry donation to the

English language.” It is a worthy donation, as well as a moving testament to a poet’s struggle to cross

from the language that gave his poetry birth into a language that has become its proverbial shelter in

the storm.

Struggle is the overall theme of the collection: to be reborn into his new language, that “wild

sea / which attacks my weak tongue” (33), into peace, where he wants to become “an ordinary man”

(35), struggle to remember even as he longs to forget the horrors of the siege of Sarajevo, to love. In

case this sounds heavy duty, the whimsical, finely wrought first poem in the book alerts us to the fact

that we are in the hands of an accomplished poet, which will make the risk of turning the next page

worthwhile.

Simic writes with the urgency of someone who has packed a lot of living into the last two

decades and needs to transpose it with the help of imagination or suffocate. Rather than a spiritual or

philosophical enquiry into the effects of violence, his poetry is a visceral tug-of-war with its twisted

offspring. Memories of the siege of Sarajevo, 1992–96, haunt his sleep, so that nightmares weave their

way through the entire collection. Civil war is compared to a mental institution, where

On the left lie those who pretend to be ill

to avoid execution.

On the right lie those who pretend to be ill

because they were chosen to execute those

on the left.

But after midnight

all the patients

play chess so nobody wins

and punish those who feel better

with a double dose of pills.

Outside of the hospital it’s worse. (22)

There is also the familiar guilt of the survivor, guilt of the deserter, as emigrants are often viewed

in times of strife by those who stay behind, guilt of wanting to be washed clean of the past. Fable,

allegory, surrealistic images and scenarios help to bring into relief the experience of being a stranger

(“The Immigrant Talks to the Slot Machine,” “What I Was Told,” “My Accent”). As a displaced

person, an exile, he longs to become visible. “Please turn off that TV and listen to my silence /

howling atop the shining antenna”(30) he begs in “Facing the TV".

Simić is at his best when he controls – but does not subdue – feverish emotion and imagination

are controlled with his craft. With a few choice surrealistic images he can place the reader in an

unfamiliar landscape with senses wide awake. Some of my favourite poems are the poignant “Spring

is Coming,” in which hope crawls out of the ruins, shell-shocked, unprepared for peace; the

allegorical “Where Is My Brick” and “Confession of the Pimp’s Cat.” “Candle of the North,” even

with its few awkward moments such as “decomposed documents of long-dead blood donors” (46)

scattered on the beach, succeeded in moving me to tears.

Not all the poems are equally successful. I was quite baffled by the poet’s decision to include

rhyming quatrains in the book, for example. Those end-of-line rhymes disturb for all the wrong

reasons. My other complaint is the occasional lapse into lugubrious excess. “Making Love” positively

writhes with twisted erotic images of “an octopus grip[ping] its victim,” screaming rooster, screaming

swan, priest’s “underwear / on the door of the orphanage” (24), which belong in the poetry of a much

younger poet. “If I Told You” offers another example

.

The bloopers are minor, however, when weighed against the rest. Canada’s poetic community

has gained an interesting voice in Simic

and his determination and energy to continue writing in

spite of the many barriers in his way can only be emulated. A word of congratulations to the

publisher, on the elegant cover and general appearance of the book. Buy it – you won’t be

disappointed.

Anna Mioduchowska’s poems, translations, stories, essays and book reviews have appeared in

anthologies, journals, newspapers and on buses, and have aired on the radio.

In-Between Season, a

poetry collection, was published by Rowan Books.

Eyeing the Magpie, a collection of poetry and art,

was published in collaboration with four fellow poets.

Buy

Sunrise in the Eyes of the Snowman at McNally Robinson Booksellers (click on the line below):

http://www.mcnallyrobinson.com/product/isbn/9781897231937/bkm/true/goran-simic-sunrise-eyessnowman

Essay published by "Globe and Mail"

First Person

Lessons from Sarajevo for Tamil refugees

Goran Simic

The Globe and Mail

Published

Back in my hometown to wash the family gravestone and meet friends, mostly writers, who never left Sarajevo, I heard a joke from the time of the siege, when the famous tunnel under the airport runway was the only way to escape the embattled city.

In the middle of the tunnel, two brothers heading in opposite directions bump into one another. They immediately begin shouting the same words: "Where the hell are you going? There is nothing there."

I still feel the weight of that question mark.

As I watch the news about the Tamil refugee claimants touching shore in Vancouver, I think of the Siege of Sarajevo, which lasted longer than the Siege of Leningrad. Though every survivor has the right to tell his own stories, I published some on behalf of the 10,000 who were killed - by the daily barrages of sniper bullets, by grenades, by hunger. Even I was killed once - when the newspaper published my name on the list of victims of the 1992 bombing of the city.

Three years of suffering

That day I felt like a ghost walking the streets, trying to persuade my neighbours and friends that I was still alive. My two children got their own portion of horror - learning to catch rainwater dripping from our ceiling holes, facing an empty fridge after the city's food supply was cut off, listening to the horrible silence of the telephone receiver after the central Tele-Post Building had its power cut. Not to mention that now, after the war, innocent fireworks still cause a sudden nausea in the stomachs of all of us who ever heard a real bomb exploding.

To talk about my three years of suffering, I need three years, with additional time for the list of family and friends I lost, but I am not a masochist.

During the Siege of Sarajevo, I began to feel a strange duality about my writing: As a poet, I want to capture reality dressed in the witness outfit; and on the other hand, I try to forget that whole part of my life.

I am in the middle again. At a poetry reading in Montreal, I was asked by a grim-looking woman in the audience whether I had ever talked to a psychiatrist after I came to Canada and I answered that I didn't, "because it's cheaper to talk to my readers." Later, speaking privately with the woman, I felt ashamed when she showed me the scars on her arm, from a bomb blast in some Pakistani city I never heard of - the city she came from.

I apologized for making a joke of her question. She apologized for asking me that question. Suddenly we became polite Canadians, but members of a club that most Canadians have nothing to do with. Especially the Canadians blind to the news from other countries, the ones who don't realize that once you deny the problems in your neighbourhood, there's a good chance that same problem will knock on your door.

Do you have a credit history? a Toronto bank clerk asks Mr. Simic

I arrived in Toronto from Sarajevo with two children and a broken former life. It didn't take me long to realize that my published books were worth nothing. I knew I would never get a loan from the bank by offering my work as collateral, as Canadian poet Gwendolyn MacEwen once attempted. Especially books written in the Serbo-Croatian language, which officially ceased to exist after my old country broke into six parts.

"Do you have a credit history?" I was asked by the bank clerk, who appeared to believe she had a mentally-ill person or just-released bank robber standing in front of her. That moment the pain in my stomach became my guide.

Instead of a loan, I was forced to find work as a labourer, loading and unloading trucks. That adventure lasted several years, till doctors advised me to give it up.

Then I became a full-time Canadian. I waited in long queues at food banks with my first-generation fellow Canadians. I waited for welfare cheques and listened to welfare clerks asking me to get a job ASAP. The humanitarian aid we received during the siege had more variety. At least there, after waiting hours for food, you might find a few bullets in your shopping bag on the way home, and surprise your kid who collects war trophies.

If I had missed becoming a Canadian, I would never have heard Ana from Poland telling me, while waiting in front of the food bank kitchen, that she worked as a cleaning lady for three restaurants to pay for her kids going to flute lessons.

'Us' and 'Them'

Or the story of the young Mexican man Rulfo, who earned his wage as a boxing partner in matches that people bet on in a private club somewhere in Mississauga. He didn't know the address because he was always blindfolded. Five hundred if he won the match. Sometimes double if he lost.

If I hadn't come to Canada, I would never have learned about the huge, invisible distinction between "us" and "them." As a Canadian still romanticizing my new beginning, I published some books that hurt me as much as my readers. Judging by the letters I received from recent immigrants, I had infected them with the old terrible illness inherent in the question: "Why do they want me if they do not love me?"

As an immigrant, I feel like I belong to the most fragile category of people. It doesn't make it any better to hear that a third of the world's population carries a passport different from their place of origin. I didn't renew my Bosnian passport after it expired. What do statisticians know about the soul?

This summer, as the Sarajevo Film Festival welcomed film stars from around the world, the city also served as a red carpet for Bosnians who live elsewhere. A third of the pre-war population now lives in other countries like Australia, Canada or Sweden. They carry a simple, mocking label: diaspora.

They are like seasonal farm workers, returning to harvest some memories, while wondering why their children would rather communicate in English than Bosnian. They think of the sharp message in the words of my friend, the poet Asim Brka: "Peace kills those who believe they survived the war."

That's the easiest way I can think of to finish my thoughts, before someone asks, "Why did you come here?" Before I start thinking about the hardest part of my life in Canada: making myself visible.

In the middle of the tunnel, two brothers heading in opposite directions bump into one another. They immediately begin shouting the same words: "Where the hell are you going? There is nothing there."

I still feel the weight of that question mark.

As I watch the news about the Tamil refugee claimants touching shore in Vancouver, I think of the Siege of Sarajevo, which lasted longer than the Siege of Leningrad. Though every survivor has the right to tell his own stories, I published some on behalf of the 10,000 who were killed - by the daily barrages of sniper bullets, by grenades, by hunger. Even I was killed once - when the newspaper published my name on the list of victims of the 1992 bombing of the city.

Three years of suffering

That day I felt like a ghost walking the streets, trying to persuade my neighbours and friends that I was still alive. My two children got their own portion of horror - learning to catch rainwater dripping from our ceiling holes, facing an empty fridge after the city's food supply was cut off, listening to the horrible silence of the telephone receiver after the central Tele-Post Building had its power cut. Not to mention that now, after the war, innocent fireworks still cause a sudden nausea in the stomachs of all of us who ever heard a real bomb exploding.

To talk about my three years of suffering, I need three years, with additional time for the list of family and friends I lost, but I am not a masochist.

During the Siege of Sarajevo, I began to feel a strange duality about my writing: As a poet, I want to capture reality dressed in the witness outfit; and on the other hand, I try to forget that whole part of my life.

I am in the middle again. At a poetry reading in Montreal, I was asked by a grim-looking woman in the audience whether I had ever talked to a psychiatrist after I came to Canada and I answered that I didn't, "because it's cheaper to talk to my readers." Later, speaking privately with the woman, I felt ashamed when she showed me the scars on her arm, from a bomb blast in some Pakistani city I never heard of - the city she came from.

I apologized for making a joke of her question. She apologized for asking me that question. Suddenly we became polite Canadians, but members of a club that most Canadians have nothing to do with. Especially the Canadians blind to the news from other countries, the ones who don't realize that once you deny the problems in your neighbourhood, there's a good chance that same problem will knock on your door.

Do you have a credit history? a Toronto bank clerk asks Mr. Simic

I arrived in Toronto from Sarajevo with two children and a broken former life. It didn't take me long to realize that my published books were worth nothing. I knew I would never get a loan from the bank by offering my work as collateral, as Canadian poet Gwendolyn MacEwen once attempted. Especially books written in the Serbo-Croatian language, which officially ceased to exist after my old country broke into six parts.

"Do you have a credit history?" I was asked by the bank clerk, who appeared to believe she had a mentally-ill person or just-released bank robber standing in front of her. That moment the pain in my stomach became my guide.

Instead of a loan, I was forced to find work as a labourer, loading and unloading trucks. That adventure lasted several years, till doctors advised me to give it up.

Then I became a full-time Canadian. I waited in long queues at food banks with my first-generation fellow Canadians. I waited for welfare cheques and listened to welfare clerks asking me to get a job ASAP. The humanitarian aid we received during the siege had more variety. At least there, after waiting hours for food, you might find a few bullets in your shopping bag on the way home, and surprise your kid who collects war trophies.

If I had missed becoming a Canadian, I would never have heard Ana from Poland telling me, while waiting in front of the food bank kitchen, that she worked as a cleaning lady for three restaurants to pay for her kids going to flute lessons.

'Us' and 'Them'

Or the story of the young Mexican man Rulfo, who earned his wage as a boxing partner in matches that people bet on in a private club somewhere in Mississauga. He didn't know the address because he was always blindfolded. Five hundred if he won the match. Sometimes double if he lost.

If I hadn't come to Canada, I would never have learned about the huge, invisible distinction between "us" and "them." As a Canadian still romanticizing my new beginning, I published some books that hurt me as much as my readers. Judging by the letters I received from recent immigrants, I had infected them with the old terrible illness inherent in the question: "Why do they want me if they do not love me?"

As an immigrant, I feel like I belong to the most fragile category of people. It doesn't make it any better to hear that a third of the world's population carries a passport different from their place of origin. I didn't renew my Bosnian passport after it expired. What do statisticians know about the soul?

This summer, as the Sarajevo Film Festival welcomed film stars from around the world, the city also served as a red carpet for Bosnians who live elsewhere. A third of the pre-war population now lives in other countries like Australia, Canada or Sweden. They carry a simple, mocking label: diaspora.

They are like seasonal farm workers, returning to harvest some memories, while wondering why their children would rather communicate in English than Bosnian. They think of the sharp message in the words of my friend, the poet Asim Brka: "Peace kills those who believe they survived the war."

That's the easiest way I can think of to finish my thoughts, before someone asks, "Why did you come here?" Before I start thinking about the hardest part of my life in Canada: making myself visible.

Review of Immigrant Blues

A Severe Elsewhere

by Ken Babstock (Books in Canada)

Goran Simic was born in Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1952, lived through the siege of Sarajevo, and came to Canada as a landed immigrant in 1996. Before leaving, he'd been considered one of the former Yugoslavia's most prominent living poets, as well as being an accomplished story writer, essayist, and playwright. He came here under the auspices of PEN Canada and was writer in residence at Massey College for a year before being forced to work, as Toronto's eye magazine recently put it "slinging boxes for Holt-Renfrew." While some of these poems first appeared in a limited edition book by Simic and Fraser Sutherland called Peace and War, this is his first full-length collection published in Canada and includes a clutch of poems written in English. The majority included here were translated by Amela Simic (not without her own very impressive list of credentials: having translated the likes of Susan Sontag, Saul Bellow, Michael Ondaatje, and Bernard Malamud into Serbian).

In this review of the poems, I am going to make a distinction between the poems translated from the poet's native tongue and those he has written directly in English. Then I'm going to qualify my distinction. I'll most likely end up qualifying my qualifications. The tags (E) and (Tr.) I'll use to identify which language the poems were written in. "Open the Door" (E) opens Immigrant Blues with this stanza:

Open the door, the guests are coming

some of them burned by the sun, some of them pale

but every one with suitcases made of human skin.

If you look carefully at the handles, fragile as birds' spines,

you will find your own fingerprints, your mother's tears,

your grandpa's sweat.

The rain just started. The world is grey.

We're immediately greeted with the psychic baggage prolonged war forces into the laps of immigrant communities, delineating, in no uncertain terms, what will be the operational terrain of the rest of Immigrant Blues. We also recognize, in those last desultory, deadpan weather reports, conveyed in robotic iambs, the tradition of mordant wit and survivalist's humour found in Eastern and Central Europe's greatest contemporary poets. (Is it too far-fetched to read the poet taking his first ironic baby steps into the literary tradition of his adopted language?) The poem concludes with an image of severe ontological uncertainty:

And you are not certain if they are ghosts

or your own shadow which you left behind

long ago after you left your home

to knock on somebody's door

on some stormy night.

This is one of the few (along with "My Accent" and "On The Bike") very successful poems that were written in English. This doesn't damage the book, as only seven are scattered throughout the twenty poems that make up the first section called "Sorrow". And it's fitting that they're placed in this section, as losing one's cultural-linguistic milieu must be an especially crushing species of sorrow. My complaint is merely that they aren't isolated as a subset, clearly distinguishable to the reader, instead of attempting assimilation with the far stronger translated pieces they sit among. Until I'd paused, at around page 30, and gone to the endnotes, I had a dimmer view of the collection of poems. Having made allowances for the daunting, and possibly life-long, project of learning to write in a second language, though, the book really comes into its own as a document of imagination's survival and surviving memory.

Simic's best poems succeed by use of a deceptive sheen of civility and even-temperedness. One senses, just under the calm, declarative tone of factuality, emotions more searing and barely contained. Having lived through war, would any expression short of howls of grief seem sufficient? The claim on sanity, continuance, and level-headedness in the face of such inner strife is a common and commendable feature of these poems:

The war is over. I guess.

At least that's what the morning paper says.

"The War is Over, My Love"(Tr)

I had never been aware I was a nation

until they said they'd kill me,

my friend told me,

who'd escaped from a prison camp

only to be caught and raped by Gypsies

"A Scene, after the War"(Tr)

Hidden behind the curtain,

I learned everything I learned

by peeking through the window.

I grieved for every death,

I was happy about every birth

and I commiserated with street Revolutionaries

"At the End of the Century" (Tr)

The second section, "Hangover" contains some gems of deep feeling, the material reaching further back toward older family members, the poet's childhood, mythopoeic retellings of the origins of civic violence, and two poems honouring and arguing with Jorge Louis Borges. These are highly confident pieces whose constellations of symbols feel intentional and powerful. The syntax takes on an elevated complexity and loses none of the directness:

Did his finger sweat while reaching for the cold trigger

where the beauty of persuasion

was turning into noise?

(...)

I am trying to unravel this

in the bark of the oak

behind which begins the world

where I don't know how to belong.

"A Note on the Forest and You" (Tr)

Some of these poems are as moving as they are illuminating with regards to the psychological ramifications of war, not only on a single author, but on an entire community living in exile-forced, or otherwise. And the troubled peace Simic builds for himself in the last two poems of the third section, "Nightmares", can be held up as evidence of the worth of the inner life: "I talked to my shadows, chatted with the river god,/and many trivial details are now behind me."

I did recoil from some of the simpler sentiments expressed in Immigrant Blues - "I'm lonely", "I often drink too much", "I often admire women from afar"-but recently I became aware of a term used with all sincerity in Europe that I'm guessing only vaguely corresponds to what we in North America would call The Romantic Poet. At a poetry festival in Rotterdam, I heard four people from four different countries (Russia, Germany, Slovakia, and Estonia) describe contemporaries as Tragic Poets. This aesthetic stance has currency there, and I suspect if Canada's towns, cities, and countryside had witnessed the same century as Europe's, we'd be more willing to listen to the lonely and dejected. Goran Simic's voice comes to us from a severe elsewhere, and we're lucky to have him now in English.

"From Sarajevo With Sorrow "- Review by Zach Wells

Clear Vision

Deceptively simple: the shopworn phrase of the blurbing

alchemist who would make gold a leaden text. When in the opening poem of From

Sarajevo, With Sorrow Goran Simic announces that he "would like to write poems

which resemble newspaper reports," the poetry connoisseur is apt to balk. Why

would anyone want that? Shouldn't the rich language of poetry be opposed to the

pinchpenny prose of journalism? Isn't this asking of poetry something that it

cannot and should not be made to do?

Nine times out of ten, the connoisseur is probably right. But the majority of British or North American poetry readers bring to a book a set of assumptions forged in relative peace, security and prosperityùisolated events such as the FLQ crisis, the Columbine shootings and the attack on the World Trade Center notwithstanding. For most Western poets, if they write about war and genocide, it cannot be in anything but an abstract manner. But for a poet who has witnessed a period of horrible violenceùand the florid rhetoric that invariably accompanies such tumultùthe exigencies of his craft are substantially different. As Theodor Adorno famously said, "writing poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric."

Paul Celan, a Holocaust survivor, responded to this challenge by writing poems of extreme indirection. As a Bosnian Serb who lived through the siege of Sarajevo (he now resides in Toronto) and whose brother was killed by a sniper, Simic takes a radically different tack: "I simply wrote what I saw." Indeed "What I Saw" is the title of one poem and vision is one of several leitmotifs that give From Sarajevo its form. Twenty-nine of the forty-four poems in this new collection appeared in 1997 in very different English versions. These versions were written by David Harsent who worked from "cribs" prepared by Amela Simic. Reading Harsent's adaptations, published by Oxford University Press as Sprinting from the Graveyard, beside these new versions (as translated by Amela Simic alone), one quickly gets the sense that Harsent was uncomfortable staying true to what Goran Simic saw. He states in his foreword that he used Amela Simic's "literal texts . . . to get what I wanted. My purpose was to make new poems in English from this raw material. . . I made changes, some extravagant; excisions, some radical; and additions, some substantial. . . There's nothing particularly new about this technique, though I think I may have taken it further than most."

And there's nothing inherently wrong with such a technique either. Poets like Robert Lowell, Robert Bly and Peter Van Toorn have created wonderful poems in English by taking substantial liberties with a text in another language. But when the subject matter of a work to be translated is the very raw material of an actual war zone, as witnessed firsthand by the poet himself, it seems to me that a far greater degree of sensitivity to formal intention is required of a translator, lest he be guilty of the sort of lyrical barbarism of which Adorno is rightfully leery.

Looking at the differences between two translations of one poem is a good way to get a sense of how Harsent goes wrong and why the new version is superior. The first poem in From Sarajevo is "The Beginning, After Everything." In Sprinting, this is the thirteenth poem; Harsent renders its title "Beginning After Everything". The placement of this poem at the beginning of the book is crucial because it contains the programmatic statement of artistic intention I have quoted above; this is the beginning, not merely a beginning. Harsent ignores this by shifting the poem to the middle of the book, altering its form and spiking its diction.

Most of the poems that were published in Sprinting are typeset in From Sarajevo as columnar prose paragraphs "which resemble newspaper reports." Harsent breaks prose into verse lines and paragraphs into stanzas, so that the poems are now only "like newspaper reports" (emphasis added). In From Sarajevo, Simic wants his poems to be "so bare and cold that I could forget them the very moment a stranger asks: Why do you write poems which resemble newspaper reports?" Harsent has jazzed this up with emphatic repetitions to read "so heartless, so cold,/that I could forget them, forget them/in the same moment that someone might ask me,/ 'Why do you write poems like newspaper reports?'" Elsewhere, a "hungry dog licking the blood of a man lying at a crossing" becomes a "ravenous dog/feasting on blood/(just another corpse in snipers' alley)." This kind of melodramatic phrasing is so patently opposed to the chilled restraint Simic espouses that one feels embarrassed for Harsent's enthusiastic bungling.

It becomes evident from comparative reading that some of the "radical excisions" Harsent has permitted himself function to cleanse the poems of references that might be particularly offensive to outside observers. This is perhaps most evident in "Love Story", a poem about two lovers from opposite sides of a bridge who are killed trying to cross it. The new English version contains the following paragraph:

"Newspapers from around the world wrote about them. Italian dailies published stories about the Bosnian Romeo and Juliet. French journalists wrote about a romantic love which surpassed political boundaries. Americans saw in them the symbol of two nations on a divided bridge. And the British illustrated the absurdity of war with their bodies. Only the Russians were silent. Then the photographs of the dead lovers moved into peaceful Springs."

The poem ends with "Spring winds" carrying the "stench" of the lovers' bodies; "No newspapers wrote about that." In his adaptation, Harsent deliberately excludes Simic's damning critique of Western nations' (countries, Simic says in his Preface, which "compensated for their dirty consciences by feeding our walking dead, while they did nothing to stop the siege") aestheticization of a war story; no countries are named and the final sentence is dropped. This is nigh censorious editing, not translation, and Harsent is guilty of it on several occasions. In the unexpurgated translation, we see one very clear reason why Simic wants to write poems "which resemble newspaper reports": because newspaper reports too often indulge in the barbaric lyrical fancies of poetry.

But we should be careful of taking Simic's stated intention too literally. What and how a poet sees is substantially different from someone else's vision. The poet has "X-ray eyes"; he sees in metaphors, in images, in allegories. And he sees not so much in pictures as in words. No small wonder that there are references in these poems to a gremlinesque angel who "rewrote the prescription for my glasses" and "officers with gold buttons for eyes [who] enter my back door and look for my glasses." For Simic, keeping his vision clear is crucial and is constantly under threat from official propaganda and the psychological trauma of living in a combat zone. Besides the cold bare facts of war, Simic's poems, as the above-quoted lines illustrate, are full of the hallucinatory facts of paranoid nightmares bred by war.

Simic is by no means aloof or self-righteous in his role as witness. In his preface, he sounds like Joseph Conrad's Marlowe when he writes that, for all the "horror that I went through . . . as a poet, I would be deeply sorry if I hadn't stayed, in the middle of horror, a witness to how cheap life can be." There is inevitably something parasitically self-serving and self-consuming in the poet's transformation of life into art, regardless of how noble that art ends up being, an irony Simic captures with sangfroid in the very unjournalistic sonnet, "I Was a Fool":

I was a fool to guard my family house in vain

watching over the hill somebody else's house shine,

and, screaming, die in flames. I felt no sorrow and

no pain

until I saw the torches coming. The next house will

be mine.

If I wasn't somebody else, as all my life I've been,

I wouldn't say to my neighbour that I feel perfectly

fine

upon seeing his beaten body. I should offer my own

skin

as a tarp. Will the next beaten body be mine?

I was a fool. I love this sentence. Long live Goran

and his sin.

There is no house or beaten man. There is no poetry,

no line,

there is no war, there are no neighbours. There's no

tarp made of skin.

But there's a pain in my stomach as I write this. It's

only mine,

this sentence, the one I swallowed, whose every

word

is each of the flames I saw, every scream a sword.

Here, the poet looks back on the conflictùboth external and internalùand manages to both damn and praise his role in it. It seems to me significant that he does this in a far more self-consciously artificial poetic form than the prose columns that predominate in From Sarajevo. This marks the poet's transition from a poetry of witness to a poetry of reflection and recollection. And it marks the move from one home and language to another, the Shakespearean sonnet being a quintessentially English form. Simic tells us in his acknowledgements that sixteen of the poems in this book he "either wrote in English or translated into English himself." Coyly, he doesn't specify which ones and I would have a very hard time trying to guess them all. If, as I suspect, "I Was a Fool" is an original English poem, then I would have to say that Canada and the English language are the recipients of a great blessing improbably born of a brutal war.

Zach Wells is the Halifax-based author of Unsettled, a collection of Arctic poems. A new chapbook of poems, Ludicrous Parole, is forthcoming from Mercutio Press.

Nine times out of ten, the connoisseur is probably right. But the majority of British or North American poetry readers bring to a book a set of assumptions forged in relative peace, security and prosperityùisolated events such as the FLQ crisis, the Columbine shootings and the attack on the World Trade Center notwithstanding. For most Western poets, if they write about war and genocide, it cannot be in anything but an abstract manner. But for a poet who has witnessed a period of horrible violenceùand the florid rhetoric that invariably accompanies such tumultùthe exigencies of his craft are substantially different. As Theodor Adorno famously said, "writing poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric."

Paul Celan, a Holocaust survivor, responded to this challenge by writing poems of extreme indirection. As a Bosnian Serb who lived through the siege of Sarajevo (he now resides in Toronto) and whose brother was killed by a sniper, Simic takes a radically different tack: "I simply wrote what I saw." Indeed "What I Saw" is the title of one poem and vision is one of several leitmotifs that give From Sarajevo its form. Twenty-nine of the forty-four poems in this new collection appeared in 1997 in very different English versions. These versions were written by David Harsent who worked from "cribs" prepared by Amela Simic. Reading Harsent's adaptations, published by Oxford University Press as Sprinting from the Graveyard, beside these new versions (as translated by Amela Simic alone), one quickly gets the sense that Harsent was uncomfortable staying true to what Goran Simic saw. He states in his foreword that he used Amela Simic's "literal texts . . . to get what I wanted. My purpose was to make new poems in English from this raw material. . . I made changes, some extravagant; excisions, some radical; and additions, some substantial. . . There's nothing particularly new about this technique, though I think I may have taken it further than most."

And there's nothing inherently wrong with such a technique either. Poets like Robert Lowell, Robert Bly and Peter Van Toorn have created wonderful poems in English by taking substantial liberties with a text in another language. But when the subject matter of a work to be translated is the very raw material of an actual war zone, as witnessed firsthand by the poet himself, it seems to me that a far greater degree of sensitivity to formal intention is required of a translator, lest he be guilty of the sort of lyrical barbarism of which Adorno is rightfully leery.

Looking at the differences between two translations of one poem is a good way to get a sense of how Harsent goes wrong and why the new version is superior. The first poem in From Sarajevo is "The Beginning, After Everything." In Sprinting, this is the thirteenth poem; Harsent renders its title "Beginning After Everything". The placement of this poem at the beginning of the book is crucial because it contains the programmatic statement of artistic intention I have quoted above; this is the beginning, not merely a beginning. Harsent ignores this by shifting the poem to the middle of the book, altering its form and spiking its diction.

Most of the poems that were published in Sprinting are typeset in From Sarajevo as columnar prose paragraphs "which resemble newspaper reports." Harsent breaks prose into verse lines and paragraphs into stanzas, so that the poems are now only "like newspaper reports" (emphasis added). In From Sarajevo, Simic wants his poems to be "so bare and cold that I could forget them the very moment a stranger asks: Why do you write poems which resemble newspaper reports?" Harsent has jazzed this up with emphatic repetitions to read "so heartless, so cold,/that I could forget them, forget them/in the same moment that someone might ask me,/ 'Why do you write poems like newspaper reports?'" Elsewhere, a "hungry dog licking the blood of a man lying at a crossing" becomes a "ravenous dog/feasting on blood/(just another corpse in snipers' alley)." This kind of melodramatic phrasing is so patently opposed to the chilled restraint Simic espouses that one feels embarrassed for Harsent's enthusiastic bungling.

It becomes evident from comparative reading that some of the "radical excisions" Harsent has permitted himself function to cleanse the poems of references that might be particularly offensive to outside observers. This is perhaps most evident in "Love Story", a poem about two lovers from opposite sides of a bridge who are killed trying to cross it. The new English version contains the following paragraph:

"Newspapers from around the world wrote about them. Italian dailies published stories about the Bosnian Romeo and Juliet. French journalists wrote about a romantic love which surpassed political boundaries. Americans saw in them the symbol of two nations on a divided bridge. And the British illustrated the absurdity of war with their bodies. Only the Russians were silent. Then the photographs of the dead lovers moved into peaceful Springs."

The poem ends with "Spring winds" carrying the "stench" of the lovers' bodies; "No newspapers wrote about that." In his adaptation, Harsent deliberately excludes Simic's damning critique of Western nations' (countries, Simic says in his Preface, which "compensated for their dirty consciences by feeding our walking dead, while they did nothing to stop the siege") aestheticization of a war story; no countries are named and the final sentence is dropped. This is nigh censorious editing, not translation, and Harsent is guilty of it on several occasions. In the unexpurgated translation, we see one very clear reason why Simic wants to write poems "which resemble newspaper reports": because newspaper reports too often indulge in the barbaric lyrical fancies of poetry.

But we should be careful of taking Simic's stated intention too literally. What and how a poet sees is substantially different from someone else's vision. The poet has "X-ray eyes"; he sees in metaphors, in images, in allegories. And he sees not so much in pictures as in words. No small wonder that there are references in these poems to a gremlinesque angel who "rewrote the prescription for my glasses" and "officers with gold buttons for eyes [who] enter my back door and look for my glasses." For Simic, keeping his vision clear is crucial and is constantly under threat from official propaganda and the psychological trauma of living in a combat zone. Besides the cold bare facts of war, Simic's poems, as the above-quoted lines illustrate, are full of the hallucinatory facts of paranoid nightmares bred by war.

Simic is by no means aloof or self-righteous in his role as witness. In his preface, he sounds like Joseph Conrad's Marlowe when he writes that, for all the "horror that I went through . . . as a poet, I would be deeply sorry if I hadn't stayed, in the middle of horror, a witness to how cheap life can be." There is inevitably something parasitically self-serving and self-consuming in the poet's transformation of life into art, regardless of how noble that art ends up being, an irony Simic captures with sangfroid in the very unjournalistic sonnet, "I Was a Fool":

I was a fool to guard my family house in vain

watching over the hill somebody else's house shine,

and, screaming, die in flames. I felt no sorrow and

no pain

until I saw the torches coming. The next house will

be mine.

If I wasn't somebody else, as all my life I've been,

I wouldn't say to my neighbour that I feel perfectly

fine

upon seeing his beaten body. I should offer my own

skin

as a tarp. Will the next beaten body be mine?

I was a fool. I love this sentence. Long live Goran

and his sin.

There is no house or beaten man. There is no poetry,

no line,

there is no war, there are no neighbours. There's no

tarp made of skin.

But there's a pain in my stomach as I write this. It's

only mine,

this sentence, the one I swallowed, whose every

word

is each of the flames I saw, every scream a sword.

Here, the poet looks back on the conflictùboth external and internalùand manages to both damn and praise his role in it. It seems to me significant that he does this in a far more self-consciously artificial poetic form than the prose columns that predominate in From Sarajevo. This marks the poet's transition from a poetry of witness to a poetry of reflection and recollection. And it marks the move from one home and language to another, the Shakespearean sonnet being a quintessentially English form. Simic tells us in his acknowledgements that sixteen of the poems in this book he "either wrote in English or translated into English himself." Coyly, he doesn't specify which ones and I would have a very hard time trying to guess them all. If, as I suspect, "I Was a Fool" is an original English poem, then I would have to say that Canada and the English language are the recipients of a great blessing improbably born of a brutal war.

Zach Wells is the Halifax-based author of Unsettled, a collection of Arctic poems. A new chapbook of poems, Ludicrous Parole, is forthcoming from Mercutio Press.

Two Fables published in "Walrus" Toronto

A DIVIDED MAN

For twenty years in a row the mechanic Tito from the town of Vlasenica in Bosnia had been named the best worker in Goose Feathers factory. Then his wife Rosa suddenly died. Some people said that she hanged herself when she found out that, instead of hair, goose feathers began growing on her legs. People just talk.

After that, Tito discovered nightlife and started leaving for work later and coming home earlier every day. His workday was getting shorter and shorter. He became afraid that one day he’d meet himself at the factory gate. One day in December this is exactly what happened.

“You lazy, good-for-nothing bastard. You’re late again. Aren’t you ashamed of all the medals you won over the years?” said the Tito who was leaving the factory. “Death to the working class,” replied the other Tito, who was coming to the factory just to collect his paycheque and go back to the pub. For a while they also met at the house, but stopped because the working-class Tito would be going to work just before the other Tito would be returning from the pub.

From then on they’d only meet on Sundays, when both of them would come to the cemetery to light a candle on Rosa’s grave. When their eyes accidentally met, they weren’t sure whether to hug each other or to pull out their knives. One Sunday in October the working-class Tito watched flocks of wild geese flying away and remarked, “Oooh, look how many feathers the factory’s going to lose.”

“Death to the working class,” commented the lazy Tito, watching the neon sign of his favourite pub, the Cooked Goose. He smiled when he noticed that the other Tito’s hair had begun to resemble goose feathers.

Some say that they never met again.

A CROW

When the morning newspaper wrote that I was killed last night, I was walking down a Sarajevo street unaware that I was dead. I never read the obituaries. I never read the birth notices. All I ever read were the crossword puzzles and the reports on politics. I found them similar.

“The troubles are over for you, you lucky guy,” Lisa the Fox, the corner store owner, told me when I entered. She’d already phoned my children, she said, to tell them that they wouldn’t have to pay for any food they needed in the next two months. For decades, every time I entered her store, she’d clean the crow shit off my jacket. What changed stingy Lisa the Fox? I wondered as I was leaving. Why was she smiling at me? Over the years I only saw her smile once, and that was when she was strangling me because she thought that I was a shoplifter.

Then my former business partner bumped into me on the street. Tito the Wolf never used that street, because he said the crows always shat on me from the trees. During the past year he’d avoided meeting me after I took him to court after he’d cheated me.”I just called your children to tell them that I put some money in their bank account for their future,” he told me quickly. Before running away, he gave me a handkerchief to clean crow shit from my jacket.

Passing the restaurant where my wife Margareta the Pig and I often lunched for many years, I saw her through the window chatting and holding hands with our long-time lawyer and friend Harry the Snake. He never missed sending me a Christmas card and never missed sending me bills. Through the window I read from her lips that she had already told the children the truth and that she’d kept her promise to love me till I died. And now I had. Then I saw her asking the waiter to give me back our wedding ring and some napkins to clean crow shit from my face. I walked away, telling her that I still loved her. But I doubted she could hear me.

“What a horrible morning,” I said to my children when I came home. Instead of kissing me as usual, my daughter Jane the Crocodile and my son Malcolm the Dingo jumped on me and threw me into the bathroom, which I’d avoided for years. While they locked the door behind me, I saw them wiping crow shit from their shoulders. With my wig.

What’s wrong with my face? What’s happened to my broken wings after I put on my jacket? What’s wrong with the morning newspaper I still have under my arm opened at the crossword puzzle facing the political news? I’m still sitting here in the bathroom. Just watching my face in the mirror. And wondering why a flock of crows sits on my roof, talking to one another in a language I’d forgotten long ago.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)